Exploring Layered Unlearning in LLMs

Introduction and Background

Large Language Models (LLMs) have excelled at their ability to learn, retain, and apply vast amounts of human knowledge. However, having an AI understand data to this scale poses serious safety risks for humanity. It has become increasingly important to develop machine unlearning techniques, a process which selectively removes information that humans want LLMs to forget. Such information includes copyright text and instructions to create hazardous materials. In an ideal world, proper unlearning should make it very difficult for models to "relearn" the unlearned information. Additionally, unlearning should isolate a topic such that even if we manage to relearn a topic, we only learn this in isolation. However, in practice, current unlearning techniques are fragile and often easily bypassed through adversarial relearning. In particular, Betley et al. (2025) demonstrates that fine tuning on a single topic may elicit broad effects on multiple topics that we attempted to forget in post-training. Furthermore, Hu et al. (2025) demonstrates that current unlearning techniques may merely obfuscate the information—suppressing the model's likelihood of generating it—rather than actually unlearning it. Moreover, they show that this such information can be relearned through novel relearning attacks.

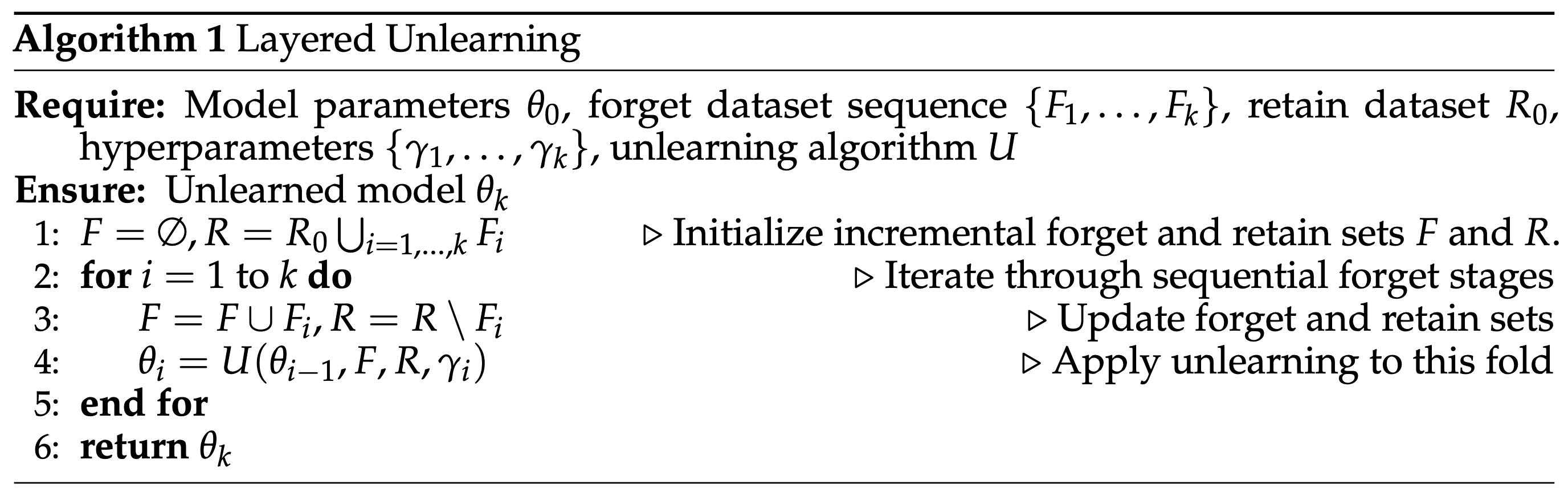

Qian et al. (2025) introduced a novel algorithm called Layered Unlearning (LU) which tries to solve the problem of adversarial relearning. Conceptually, LU unlearns a forget data set in layers (that we will now refer to as "folds"), rather than all at once. The below image is taken from their paper, which rigorously presents the algorithm.

As a practical example, we can imagine this to be a dataset containing 3 distinct subjects: bioweapons, hacking, and personal data. We start by attempting to forget bioweapons, but try to retain hacking and personal data. In the next iteration, we add the hacking dataset to the forget set and remove it from the retain set. We repeat until we have forgotten all of the information.

Research Questions and Motivation

Weighted Layered Unlearning

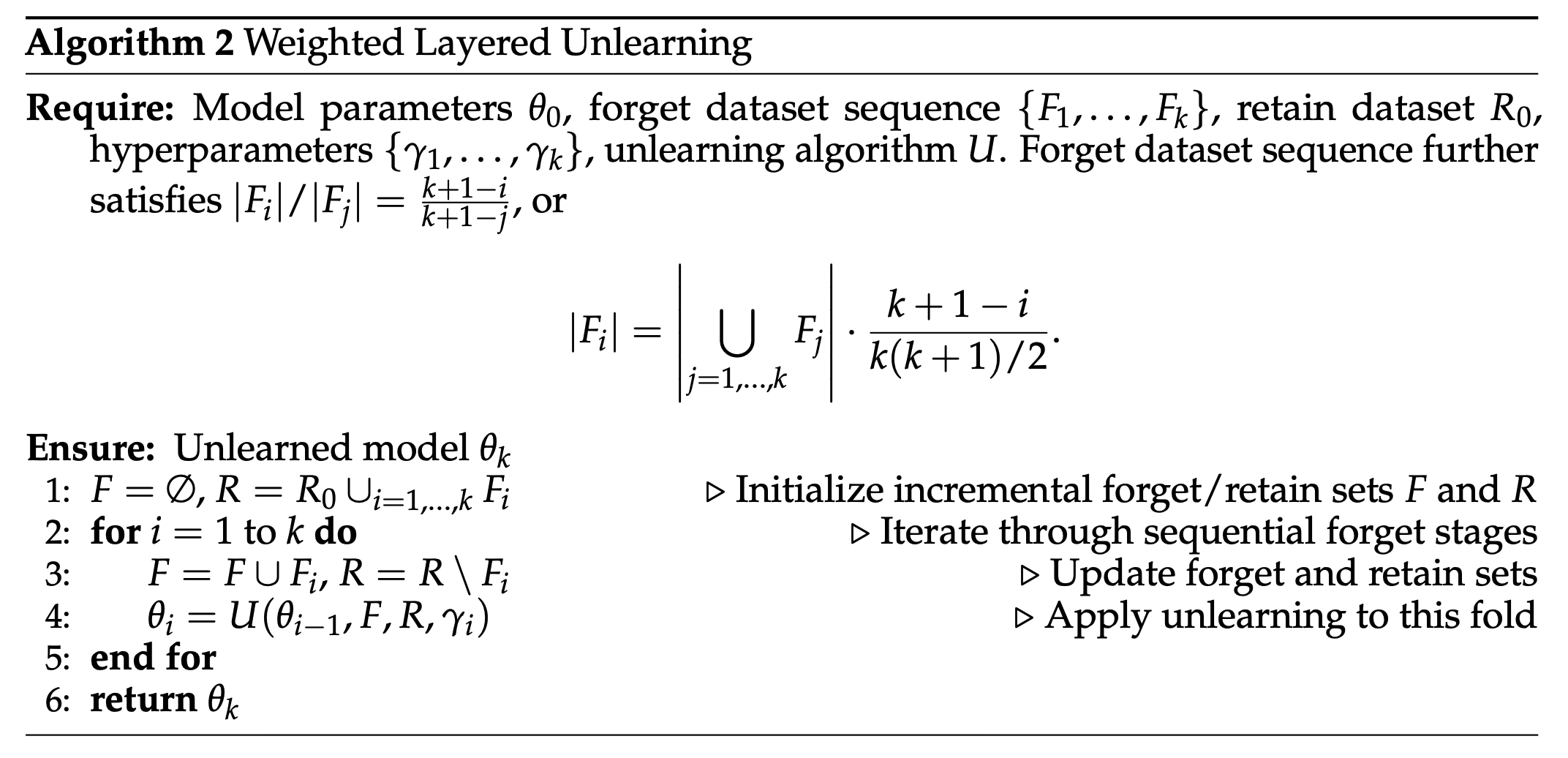

One question about the LU algorithm that naturally arises is the unevenness of data unlearning. For example, we will only spend one iteration unlearning the last dataset in the sequence whereas we will spend multiple iterations unlearning the first dataset in the sequence. Moreover, for half the datasets in the sequence, we spend more time trying to retain them than unlearn them.

We propose a simple but novel modification that we hope will alleviate this problem. The modification comes from the intuitive understanding that the time it takes to unlearn a set of information is directly proportional to the set's size. More specifically, we weight the size of a forget dataset proportionally to the amount of iterations we spend unlearning it in order to give each fold an "equal" layer of protection. That is, $|F_i|\propto k+1-i$. We describe our modified algorithm, called Weighted Layered Unlearning (WLU) below.

Semantically Related Topics

The beauty of the LU algorithm is that it forces the model to learn separate mechanisms that inhibit knowledge on each specific fold, not just the entire dataset in general. While LU effectively forces the model to construct distinct inhibition mechanisms for specific data folds, a critical gap remains in understanding the importance of the ordering of the forget dataset sequence. This is particularly evident when unlearning semantically related topics. For example, we would intuitively expect that unlearning a subject like mathematics would inherently degrade a model's proficiency in physics, given the high degree of shared representations between the two domains. Given that our own brains tend to have shared inductive biases between these subjects, we investigate whether their placement in the forget dataset sequence impacts the model's post-unlearning results.

- Semantic Clustering: Does clustering related topics (i.e. unlearning them at consecutive or close indices in the forget dataset) result in a cleaner, more complete erasure of the topics?

- Semantic Spacing: Conversely, does unlearning them at spread out indices (with unrelated topics in between) yield better and more stable results?

This research moves beyond simple data deletion to explore the optimal topology of the unlearning sequence, aiming to maximize erasure on related concepts.

Research Methods and Results

In this section, we give a formal overview of our research methods and results.

Methods

Firstly, the dataset we will use for all our experiments is the MMLU dataset. Our data was trained using the MIT ORCD Engaging Cluster. For compute, we used an Nvidia L40S and an Nvidia H100. We trained on $3$ models, all taken from HuggingFace. They include:

- Q3-06: Qwen/Qwen3-0.6B (0.6 billion parameters)

- Meta: meta-llama/Llama-3.2-1B (1 billion parameters)

- Q3-17: Qwen/Qwen3-1.7B (1.7 billion parameters)

For future reference, we will only refer to the models by their above abbreviations.

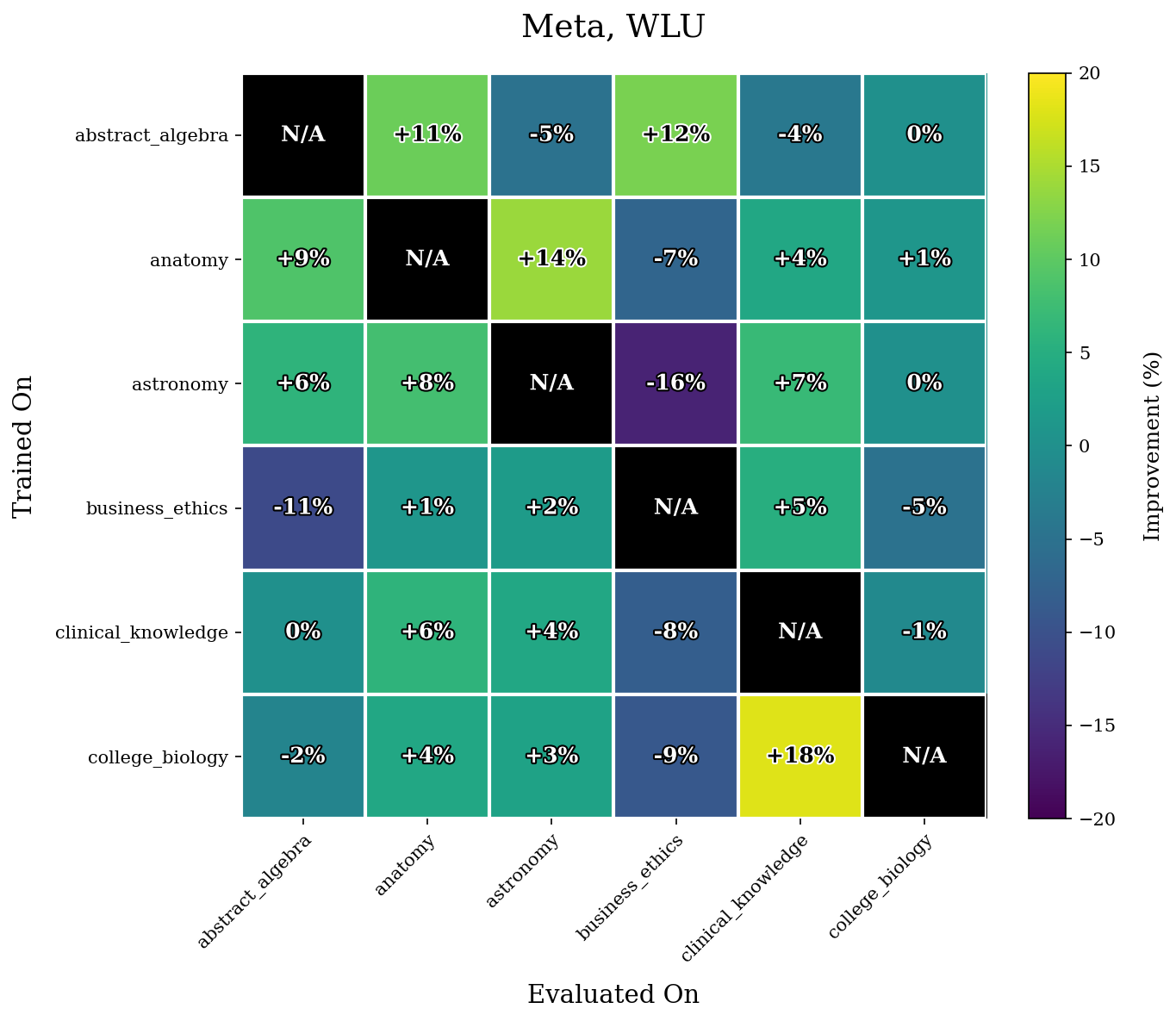

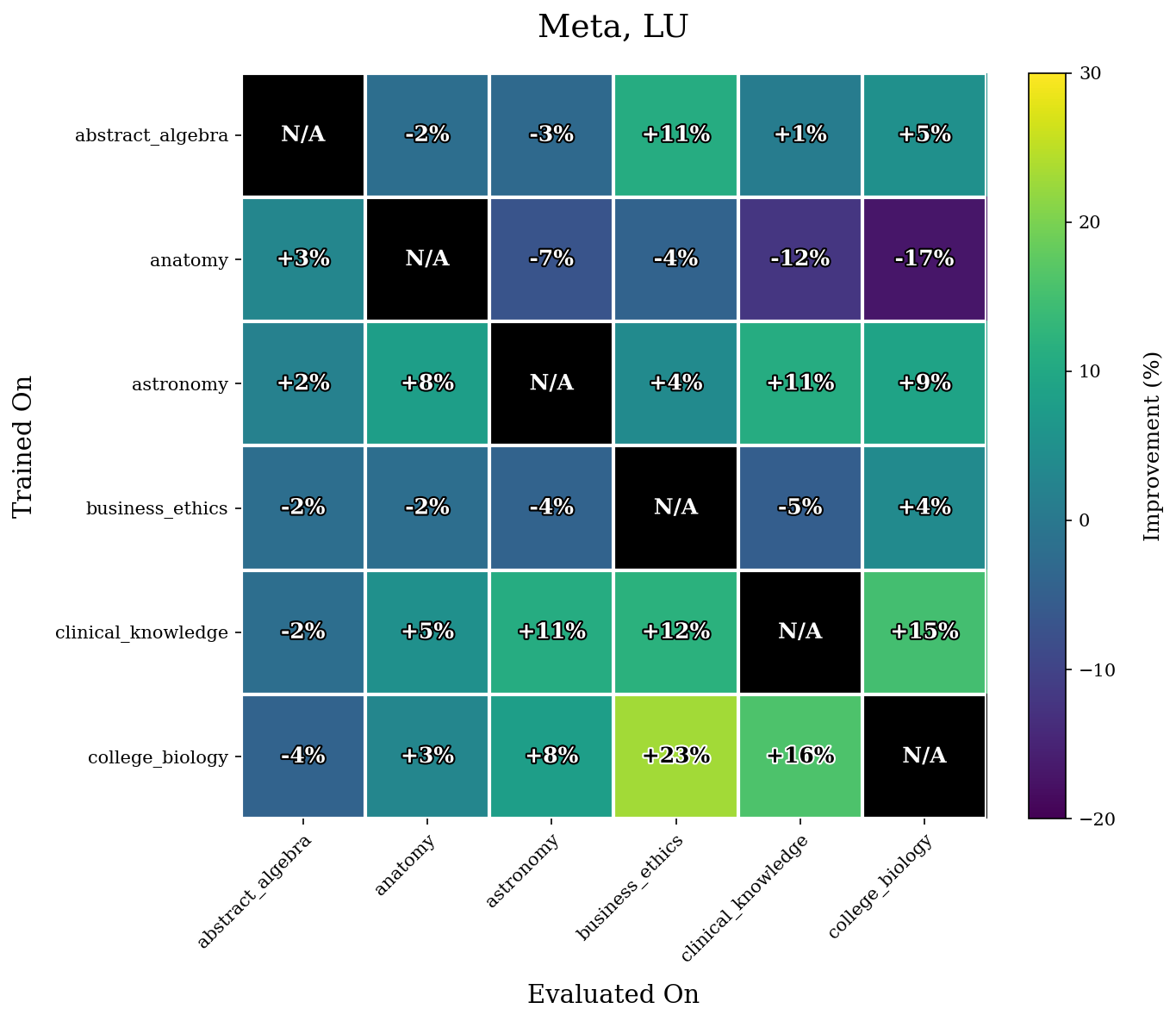

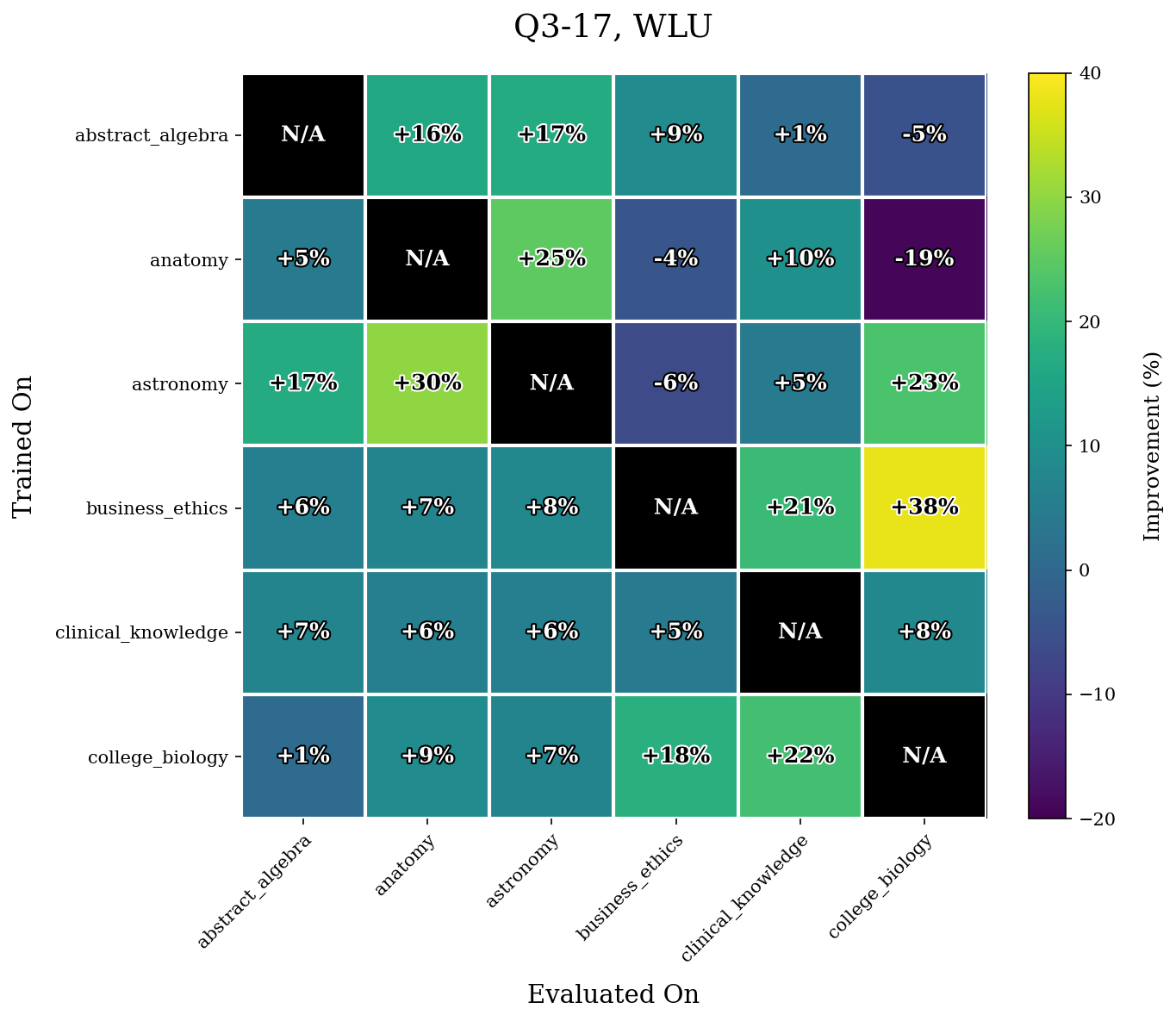

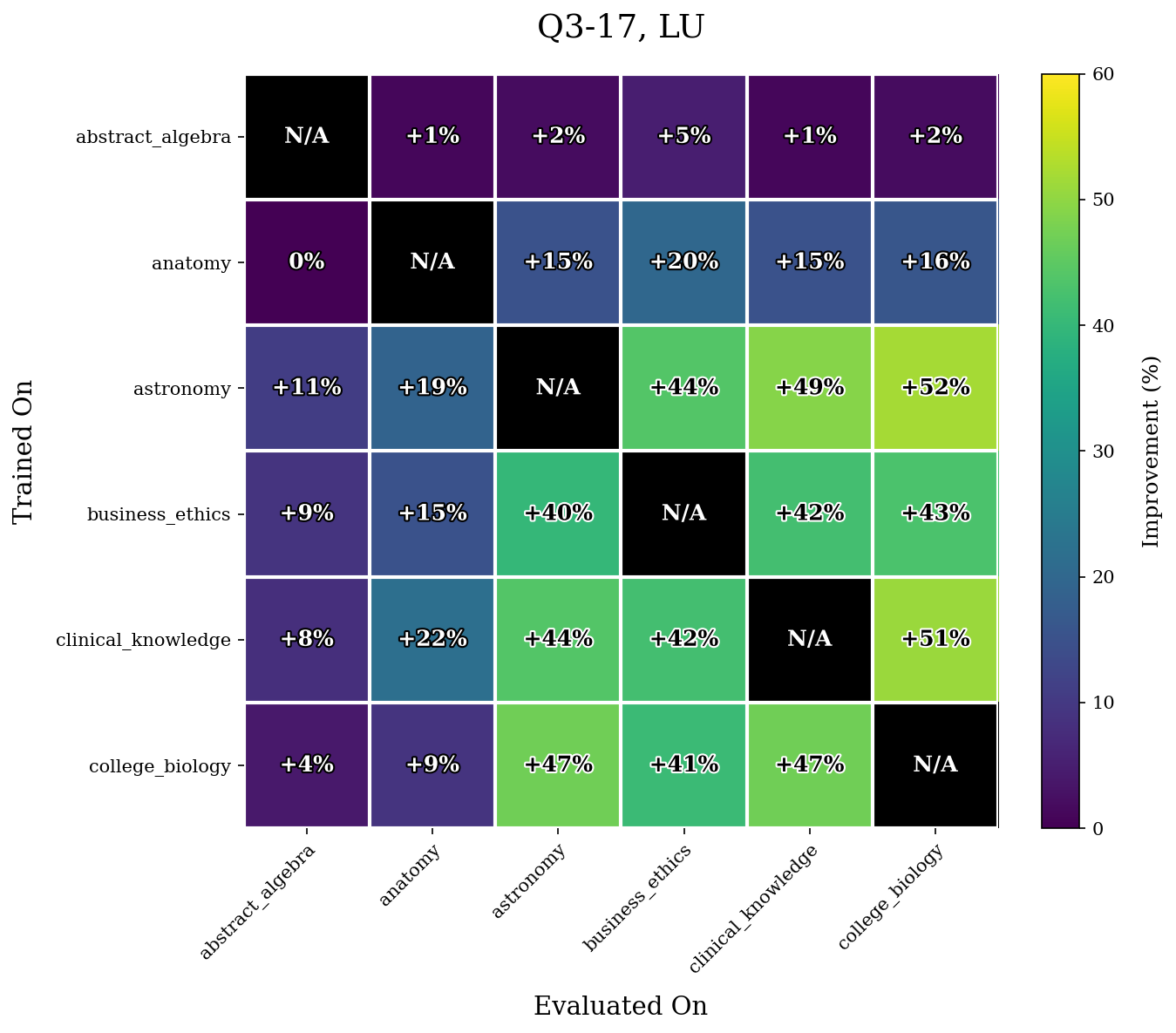

The high level approach for our experiments that readers should keep in mind is: unlearn $\to$ relearn $\to$ MCQ-based evaluation.

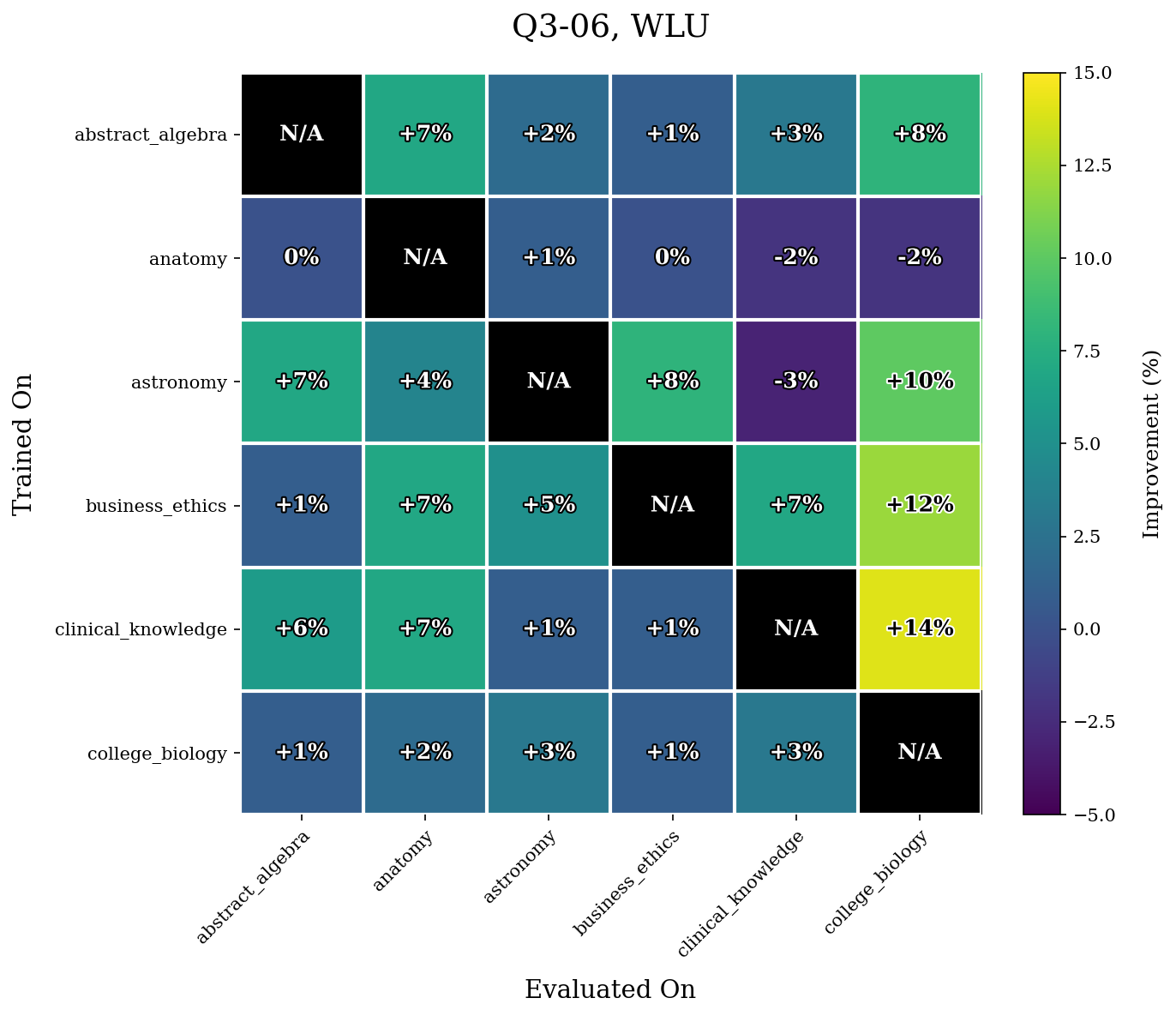

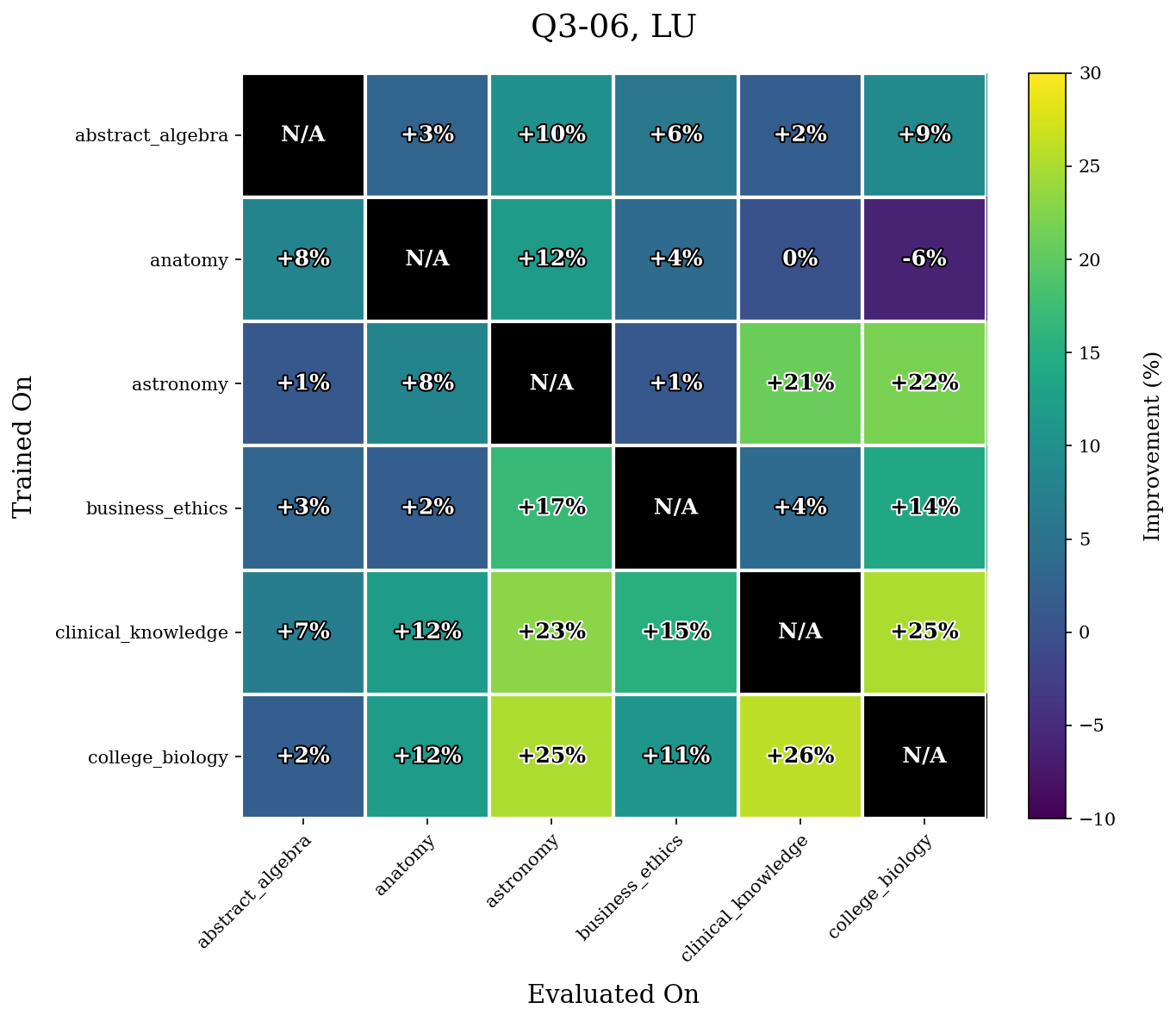

We have reimplemented LU and implemented the modification which turns it into WLU. We chose the subjects from the MMLU dataset to test our algorithm on. For testing LU and WLU, we chose $6$ different subjects to train on, and we train from $50$ questions in each subject. These are the first $6$ subjects on the MMLU dataset to standardize. In our implementation of our WLU algorithm, $3$ of the subjects will be in the first forget dataset, $2$ of the subjects will be in the second forget dataset, and the last subject will be in the final forget dataset. In the LU algorithm, each forget set will contain $2$ subjects. Certain subjects will inevitably have high degrees of overlap (such as anatomy, biology, and clinical knowledge), which will test the model's ability to combat adversarial relearning. Our approach to evaluation for this question will be the same as the one used by Qian et al. (2025) for his experiments on the Zephyr-7B-$\beta$ model. Specifically, after we unlearn, we relearn on each subject and evaluate our performance on other subjects. This is because the point of the LU and WLU algorithm is to combat adversarial relearning. Of course, the performance on the relearned subject is irrelevant to our testing as we want to see how retraining on a single fold will impact different folds. We will compare the relearning performance of the model between the WLU algorithm and the LU algorithm.

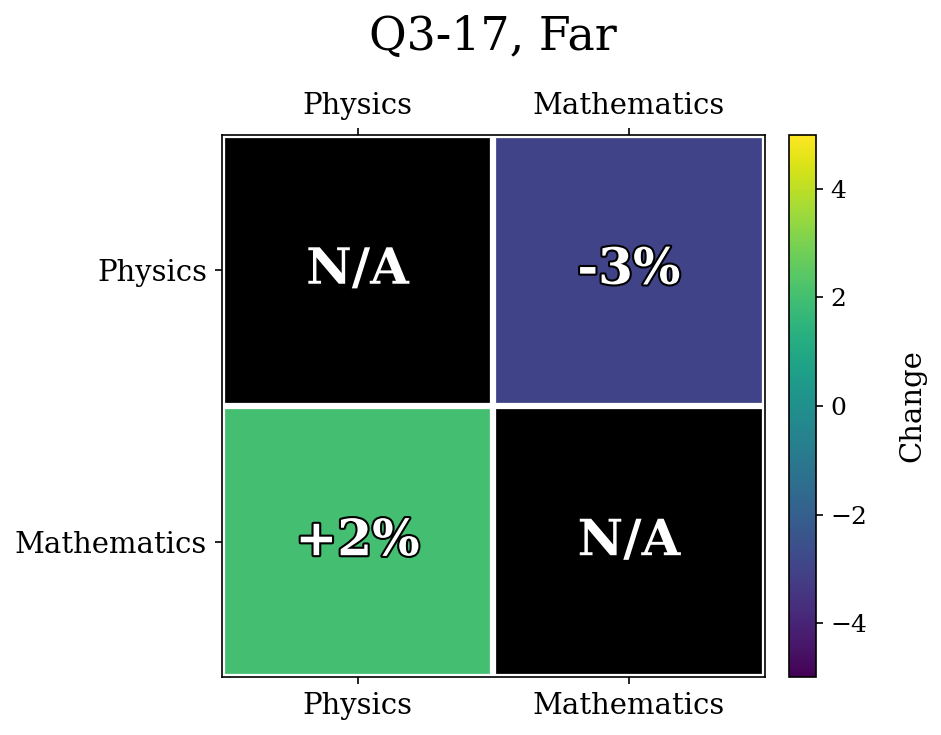

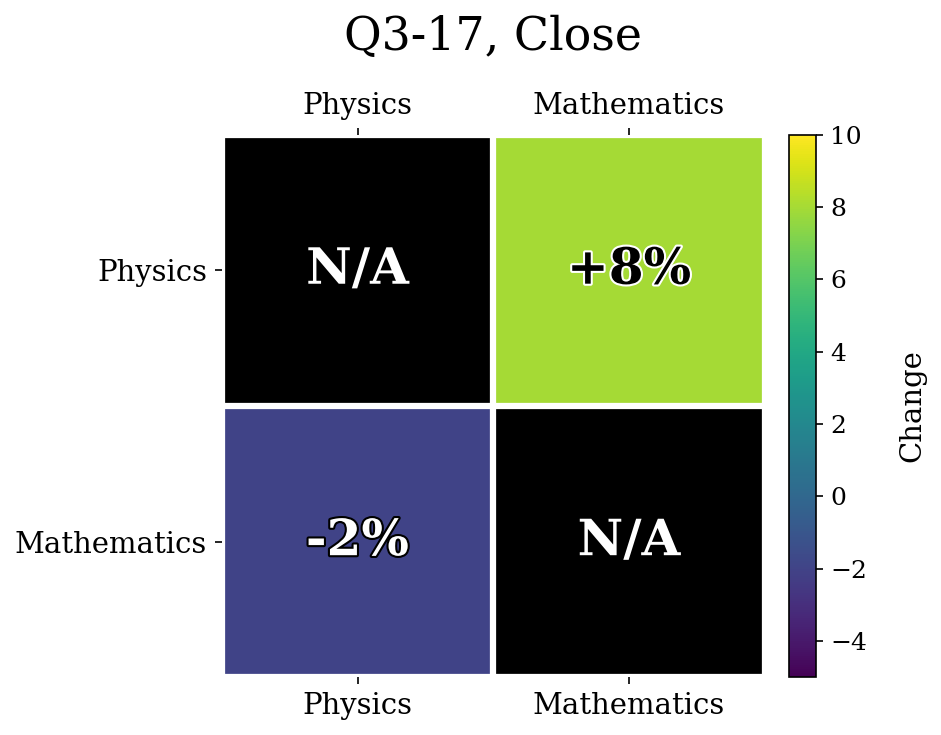

For the question about semantically related topics, we plan to use the original LU algorithm. Specifically, we will unlearn specific topics from the MMLU dataset with $k=4$ folds using two different forget dataset sequences. These two sequences are shown below.

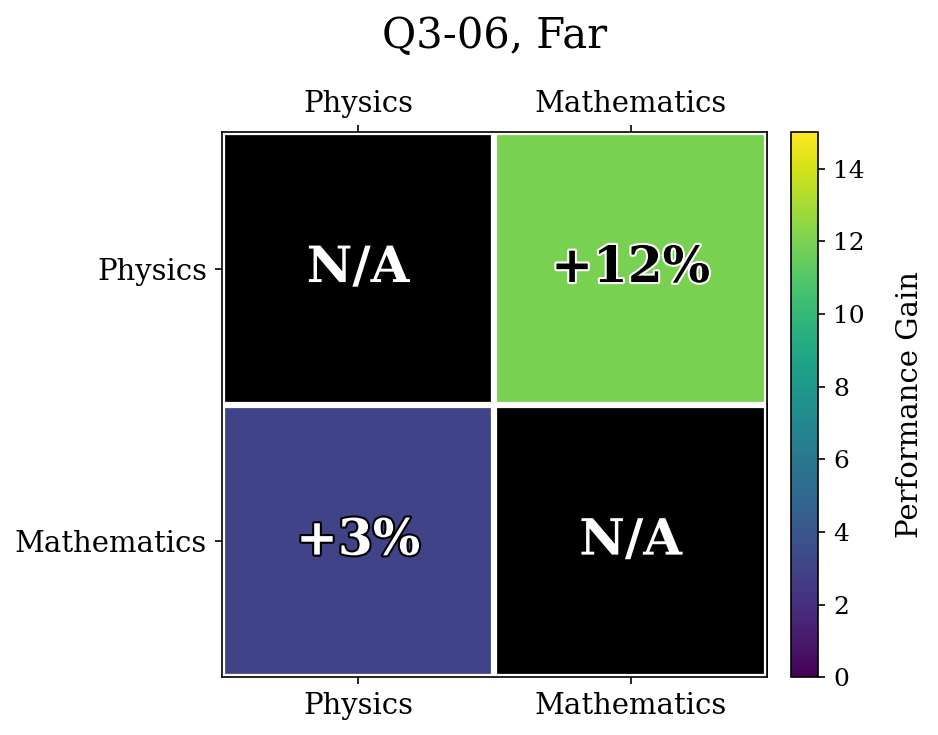

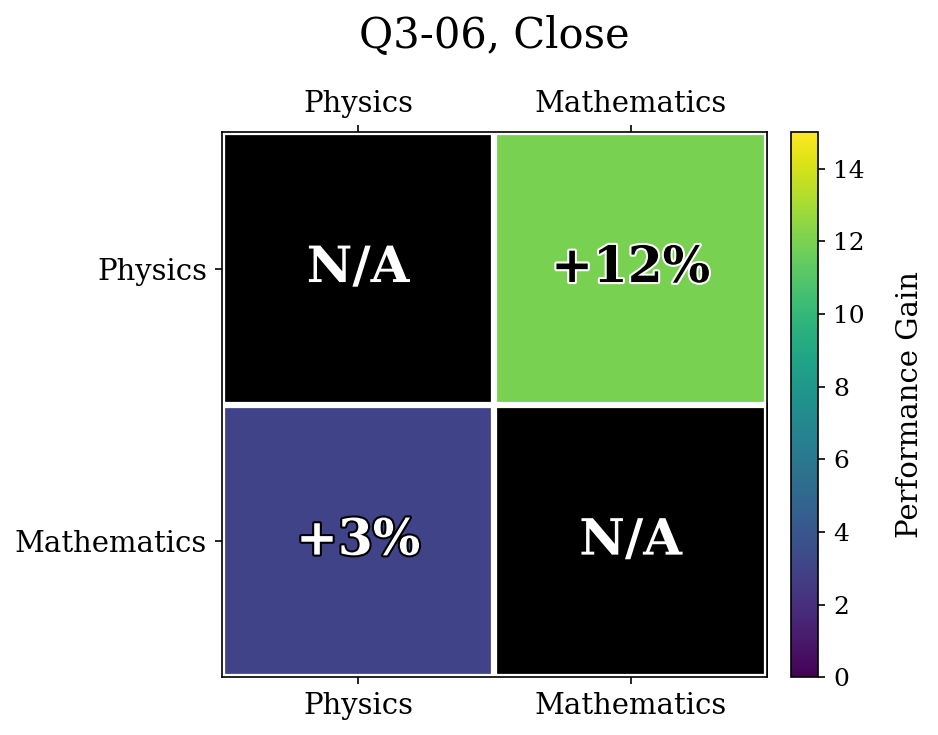

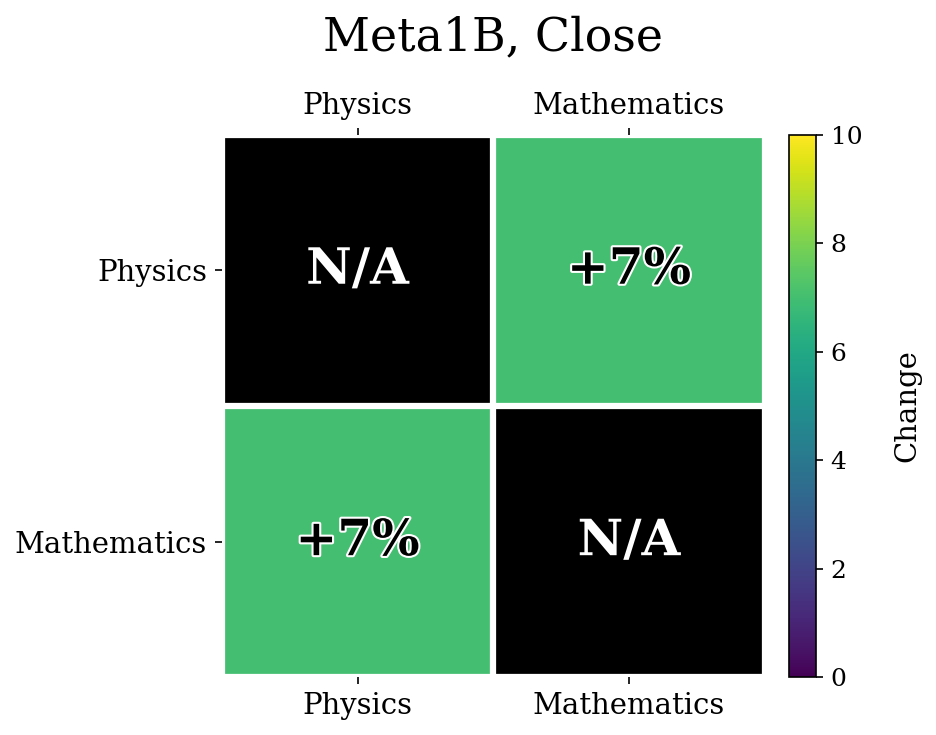

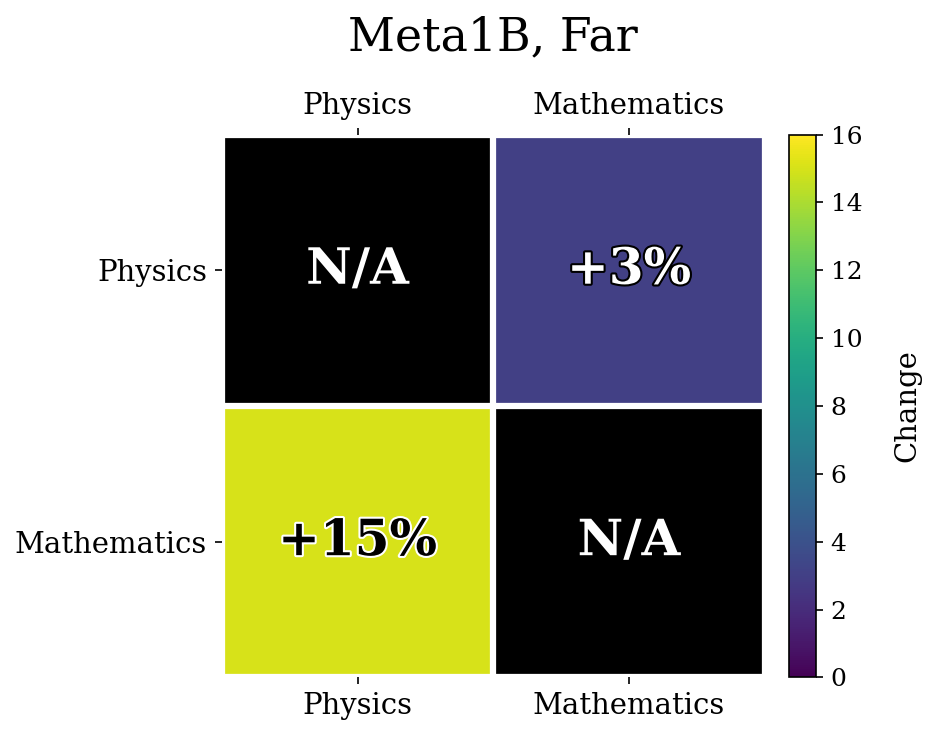

- College Physics, Psychology, U.S. Foreign Policy, College Mathematics

- College Physics, College Mathematics, Psychology, U.S. Foreign Policy

As shown, one sequence has the semantically related topics (math and physics) in consecutive indices, whereas the other sequence places them far apart. For our evaluation, we will attempt to relearn physics and then see the performance on math. We will also attempt to relearn math and see the performance on physics. We do this for both forget sequences after unlearning.

Our specific "performance evaluation" after relearning will be a simple MCQ evaluation. The respective model will be given $100$ MCQ questions and will be asked to output its answer in exactly $1$ token. Its performance will be the number of questions answered correctly divided by $100$. A lower performance means better unlearning results, as the model has difficulty relearning.

We unlearn the training data using NPO (Negative Preference Optimization) and then attempt to relearn the data using DPO (Direct Preference Optimization). NPO can be viewed as DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) without any positive samples. We can see this difference in their loss functions.

\begin{align*} \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{DPO}}&=-\mathbb{E}\left[\log\sigma\left(\beta\log\frac{\pi_\theta(y_w\mid x)}{\pi_{\mathsf{ref}}(y_w\mid x)}-\beta\log\frac{\pi_\theta(y_\ell\mid x)}{\pi_{\mathsf{ref}}(y_\ell\mid x)}\right)\right] \\ \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{NPO}}&=-\mathbb{E}\left[\log\sigma\left(-\beta\log\frac{\pi_\theta(y\mid x)}{\pi_{\mathsf{ref}}(y\mid x)}\right)\right]. \end{align*}In particular, in the DPO loss function, $y_w$ is the winning response and $y_\ell$ is the losing response. We select NPO as our unlearning function for its stability in contrast to the more standard approach, gradient ascent. Indeed, Zhang et al. (2024) gives significant empirical evidence that gradient ascent has significantly higher probability of suffering a catastrophic collapse of the model's abilities on several unlearning tasks and that NPO manages to forget more than other methods. This idea can also be justified theoretically since gradient ascent maximizes loss on the forget set, which means it naturally leads to more unbounded results. In particular, Zhang et al. (2024) gives a linear bound for gradient ascent's collapse rate to the retain dataset, whereas NPO is shown to have a logarithmic bound. We used $1\cdot 10^{-6}$ as our learning rate, as it showed us to give the best results.

Results

We first give our results for the WLU task.

Now, we show our results for the semantically related task.

The unlearned accuracies were Physics: $6\%$, Mathematics: $14\%$ for Close.

The unlearned accuracies were Physics: $4\%$, Mathematics: $40\%$ for Far

The unlearned accuracies were Physics: $4\%$, Mathematics: $8\%$ for Close.

The unlearned accuracies were Physics: $1\%$, Mathematics: $10\%$ for Far.

The unlearned accuracies were Physics: $9\%$, Mathematics: $21$% for Close.

The unlearned accuracies were Physics: $8\%$, Mathematics: $57\%$ for Far.

Analysis

We would first like to touch on our choice to not use the Tinker API, which was available to us for free usage. The Tinker API uses LoRA for fine-tuning LLMs. Many papers, including Biderman et al. (2024) and Shuttleworth et al. (2025) find that LoRA often yields suboptimal results as compared to full-rank updates. Specifically, these studies show that while LoRA is computationally efficient, it creates a more "superficial" forgetting layer than a complete erasure. Intuitively, this should be the case as we only update the last few layers in LoRA. As a result, we chose to do our own fine-tuning of models, using NPO and DPO as mentioned above, and not use the Tinker API.

Weighted Layered Unlearning

Our results show that WLU performs nontrivially better than LU. For example, in Q3-06, WLU only achieved a maximal $14\%$ increase in performance for a task whereas LU yields multiple increases $\geq 20\%$. The difference is even more stark in Q3-17. LU performs quite poorly on this model, and achieves many accuracy increases $\geq 40\%$ after retraining. The performance of WLU is much more stable, and mostly achieves accuracy increases around or under $10\%$.

As mentioned before, we hypothesize this has to do a lot because of the more evenly distributed unlearning that WLU performs.

Semantically Related Topics

Unfortunately, we found no significant difference in performance between clustering semantically related topics and spreading them out. For example, in Q3-06, having the semantically related topics close and far yielded no difference in results.

One possible reason for the lack of results is because of our small dataset. We trained on only around $50$ questions for each subject in the MMLU dataset. It may be the case that only having $2$ semantically related topics in between math and physics may not be enough to create a noticeable difference in performance. Perhaps more diversification into the humanities, arts, and other miscellaneous topics would have yielded better results.

Another possible reason was because the later forget sets in the training runs had high variance in the unlearning accuracies. For example, Q3-17, Far finished with $57\%$ accuracy on Math, whereas Q3-17, Close finished with only $21\%$ accuracy. Because the starting points were so different, comparing the relative relearning gain may be influenced by a confounding variable.

Conclusion and Further Directions

Our research on WLU vs LU shows improvements for WLU for all the models we tested on. We hypothesize this is likely due to the more evenly distributed unlearning that WLU performs, and believe that future improvements will likely be those that maintain the layering but make the process of unlearning even more uniform. Our research on semantically related topics shows ambiguity in if an ordering is better than the other. However, we do not rule out the idea of the two actually being ambiguous. In order to solve this though, for future research directions, we suggest training with significantly higher values of $k$ and diversifying to multiple semantically related topics, not just math and physics.

As for further directions not discussed previously, one possible further direction of research lies in the idea of a periodic method of unlearning and relearning. Discussing the topic with Qian, he mentioned that one possible area that he did not pursue but he believes is promising is an alternating pattern of unlearning and relearning, in order to develop distinct inhibitor mechanisms for each fold. However, one issue in which arises is how to construct this alternating pattern such that each fold (dataset) in the sequence receives an appropriate amount of time to unlearn and relearn. This issue, again, lies in the inherent sequential nature of the forget sequence. Another important design choice is then how to actually combine these inhibitors to create a "global inhibitor" for each fold. This is an area in which we could not figure out during the short time we had to do our project, but is something we will definitely keep in mind for the foreseeable future.

Other, more minor directions include further tinkering with our WLU algorithm. One possible direction is to try different weightings of sets, such as quadratic or $n\log n$. Another possible direction would be to implement our algorithms with different unlearning algorithms, such as gradient ascent or representation engineering. Finally, one way to scale this project up is to try to train on bigger models and more complicated datasets and forget sequences.

We encourage anyone interested in this blog post to experiment with these ideas and let us know about their results and progress!

References

[1]Jan Betley, Daniel Tan, Niels Warncke, Anna Sztyber-Betley, Xuchan Bao, Martín Soto, Nathan Labenz, and Owain Evans. 2025. Emergent Misalignment: Narrow finetuning can produce broadly misaligned LLMs. Preprint, arXiv:2502.17424.

[2]Dan Biderman, Jacob Portes, Jose Javier Gonzalez Ortiz, Mansheej Paul, Philip Greengard, Connor Jennings, Daniel King, Sam Havens, Vitaliy Chiley, Jonathan Frankle, Cody Blakeney, and John P. Cunningham. 2024. LoRA Learns Less and Forgets Less. Preprint, arXiv:2405.09673.

[3]Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Steven Basart, Andy Zou, Mantas Mazeika, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. 2021. Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding. Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

[4]Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Steven Basart, Andrew Critch, Jerry Li, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. 2021. Aligning AI With Shared Human Values. Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

[5]Reece Shuttleworth, Jacob Andreas, Antonio Torralba, and Pratyusha Sharma. 2025. LoRA vs Full Fine-tuning: An Illusion of Equivalence. Preprint, arXiv:2410.21228.

[6]Ruiqi Zhang, Licong Lin, Yu Bai, and Song Mei. 2024. Negative Preference Optimization: From Catastrophic Collapse to Effective Unlearning.

[7]Shengyuan Hu, Yiwei Fu, Steven Wu, and Virginia Smith. 2025. Unlearning or Obfuscating? Jogging the Memory of Unlearned LLMs via Benign Relearning.

[8]Timothy Qian, Vinith Suriyakumar, Ashia Wilson, and Dylan Hadfield-Menell. 2025. Layered Unlearning for Adversarial Relearning. Preprint, arXiv:2505.09500.